When I was a kid, I never got to celebrate Halloween, or at least it seemed. My parents have home movies of me and my sister in costumes made from Butterick patterns – Jean was a witch with orange yarn hair hanging from her pointy black felt hat, while the four-year-old me was a ghost with a great big black “BOO” sewn across my front. The next year, I was a bride, and being in first grade, I was eligible to march in the elementary school Halloween pageant. I barely made it through that day at school, and by the time afternoon trick-or-treating came around, I was home in bed with a fever.

That was the start of the sick streak. Like clockwork, I’d come down with the flu, or a cold, or general malaise, during the fourth week of October. Like clockwork, I’d beg my mom to let me go trick or treating nonetheless, and like clockwork, I’d be stuck in bed, listening forlornly as other kids came to ring our doorbell and shout gleefully for treats.

It wasn’t so much the loss of candy that frustrated me. It was the loss of an opportunity to be creative. Every fall, I’d come up with a great costume idea, only to be disappointed, betrayed by my own body. But one year was different.

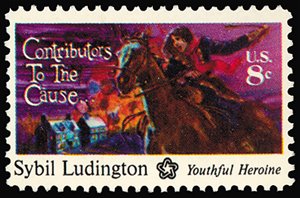

As the U.S. was starting to get Bicentennial fever, I found the perfect costume idea. I’d be Sybil Ludington. Who didn’t know Sybil? She was the teenager who, in 1777, basically pulled a Paul Revere to organize the militia after a British attack on Danbury, Connecticut. I already had a tri-corner hat from a visit to Philadelphia, and my mom had made me a cape the year before. Conveniently it was made of red, white and blue fabric.

All I needed was a horse. Hmm. Inspiration struck in the form of brown trash bags, some old boxes and a roll of masking tape. After a bit of engineering, I had my horse, complete with a hole in the middle so I could slip it over my head down to my waist. I was set for Halloween!

Then, as the date approached, I felt the flu coming over me. I fought it as much as I could, but on October 31, I had to concede. I was weak and weary, and there was no way I could go to school. It was hopeless.

I was resigned to having all of that good work go to waste, but I still half-heartedly petitioned my mom to let me go trick-or-treating for a half hour, just to take the horse out for a trot. I knew there was no chance; she was the type of parent who firmly believed the truant officers would see me out gallivanting and would send HER to reform school as punishment. A stickler for the rules, she was, and heavily motivated by shame.

Imagine my surprise when she took pity on me and said, sure, go out. Just be careful, and if you start feeling sick, come home. I didn’t give her a chance to change her mind. Faster than you could say “The British are coming,” I donned my cape, hat and horse and was out the door.

The truant officer wasn’t on the street, but some of my classmates were, jibing me for trick-or-treating when I didn’t go to school, as if they wouldn’t have done the same. Despite my declining energy, it was great to be out there, knocking on doors and collecting candy. Countless times I told people no, I wasn’t Paul Revere, and educated them about Sybil Ludington. And several nice people gave me a candy bar for me, and another one for my horse. Not a bad deal all together.

Looking back, I don’t think I lasted 15 minutes before I started feeling queasy, so it’s a good thing I had the horse to increase my draw of loot. Unlike my costume’s inspiration, I might have gotten three blocks or so in my route, but as I walked home, I felt as if I was on the victory lap. I’d finally gotten to go trick or treating, and I’d spread the word on Sybil Ludington, a significant footnote in American history.

The funny thing is that after that year, I was healthy every Halloween, just as I was getting too old for trick-or-treating, anyway. I guess that’s the breaks.